I’ve been at this documentation thing since the mid-1980s. This document is due in no small part to the work I’ve participated in at Compaq, Microsoft, and Autodesk in the 1980s and 1990s with great people from whom I’ve learned a lot. In those early days, we made it up as we went along. Use the suggestions here as a starting point and make it your own.

So you’ve been asked to devise a plan to document…something. The software, SaaS, website, and work instruction techniques are similar. Right off, don’t panic. You know more than you think you do. Based on experience, you probably have a good idea of how long it takes you to get to a first draft. Remember that making the doc plan match the schedule isn’t your job. That’s what the overall project manager does. Your job at this point is to determine what is required and what you can do to offer alternatives. Base your alternatives on changes in time, resources, and scope. It’s up to the stakeholders and project manager to determine what is acceptable for the release and what can wait until the next go around. Nevertheless, they’ll depend on your estimates — your plan — to decide. But that’s getting ahead of things. Let’s look at what goes into a good documentation plan, section by section.

Overview

In this section, tell the reader why this document exists. Ask yourself three key questions:

- What is the business case for the product?

- How will it be marketed?

- What is the purpose of the documentation, and who is it for Give the reader the background for both the project and the documentation.

Scope

What is ‘in scope’ and what isn’t? Tell the reader what you will cover with your documentation. Establish your boundaries and have stakeholders agree to them. For example, you might say that this documentation project will rebrand and reformat a recently acquired product, and any changes to the writing style or what is covered are out of scope for this release. You can change the scope as the project progresses, but give the reader the limits here.

Assumptions and Constraints

Stakeholders go into a project with assumptions that affect planning, content, and development. Do these assumptions match what you’ve been discovering? If so, relate how they affect the documentation. If not, talk with stakeholders. What about constraints? Constraints often involve the lack of resources, such as not enough writers at the right time, incomplete features, and the like. How will you deal with this? How do you see the constraints affecting delivery?

The Project Statement of Purpose

What is the product documentation for — what is the purpose? Do you want to reduce support costs? Are you introducing the software to a new audience? How will the documentation relate to the software, hardware, or services? This is the “10,000-foot look-down” at the documentation and the product. Relate this statement to the scope, assumptions, and constraints. Anyone reading these sections should have a better understanding of your documentation project.

Target Audience

You’ll fail if you don’t know who you’re writing to. Take the time — make the time — to discover the audience. Some resources are right in your office. Talk to the product support team if you’re documenting a product update. Marketing and sales are other good sources of data. They need to know who they’re selling to, what problems the product solves, and why it is better than the competition. Ask for their input and advice. If your company offers training, ask to sit in on training for the existing version with real users. If this is an update, ask to talk with users.

Users

With this information, you can start building a picture, sometimes called personas, of your users. Create user stories describing how they’ll use the product and documentation. What do they want to do? What do they want to know? What do they care about? These answers help you define the documentation and what you must include. Remember, good documentation doesn’t just describe features. Good documentation helps the user accomplish her goals quickly and efficiently.

Task Descriptions

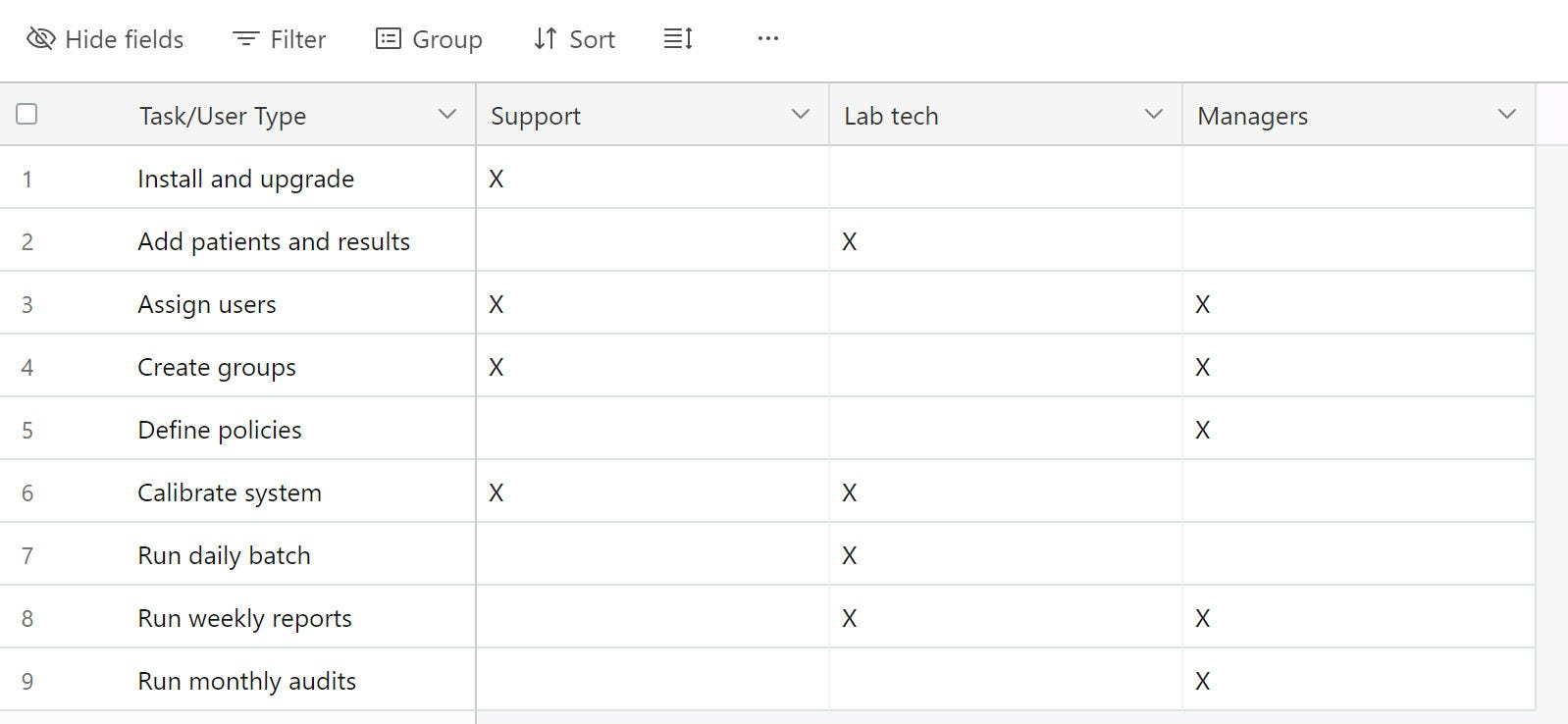

Along with defining the users, you need to define user tasks. This feeds into the usability goals and requirements. This section tells the reviewers what the document will teach. Do you have to support multiple user types? Create a task matrix to show what information is for what user type. For example:

Anyone looking at this table can easily see the types of users you expect and what tasks they’ll perform. It’s also easy to make changes and add more user types and tasks.

Usability Goals

Explain how the organization makes the documentation successful. This is a what, not a how or why section. What must the user guide accomplish? What will having context-sensitive help do? Take a look at the product requirements for some ideas. If a requirement is “Users will be able to query the database for a report on specimens rejected for rerun,” tell how you will document that. Group all related requirements together to help organize the documentation.

Existing Documentation

Look at existing product documentation. Again, talk with support, training, and sales and marketing. Ask to see and use any internal quick references or “cheat sheets” they’ve used.

Development and testing have their documents and plans. Examine them for anything you can use to create your plan. If you can link a task or deliverable to their plans, that would be all the better.

Product Design Implications

The user interface affects how you document the product. A product that relies heavily on scripting will need documentation that is different from that of a menu-based product. Pushing for context-sensitive Help can affect product development, as you may need a developer to help implement this.

Document Specifications

This section should give the reader a good idea of what the documents will look like.

Platforms Supported

If you need to support multiple operating systems, describe the differences here. This is especially important for Windows vs. Macintosh vs. a web-based delivery. Are there any trade-offs you need to make? If you provide online delivery for multiple targets or platforms, factor in the additional testing time.

Graphics and Media

Will you include screenshots, conceptual art, diagrams, flowcharts, etc.? How will you produce them? Call-outs and any modifications take time. Be sure to estimate and track that. If you will include video, consider disk space and download speed. And don’t forget localization — text needs to be translated, which often means redoing images.

Delivery

If your project is delivered online, you don’t need to worry about disk space, printing, or storage costs. Indicate how it will be delivered online, how the document store is provisioned, and what steps must be taken.

Discuss the issues that impact time and delivery for print, PDF, and online Help that ships with the software. Stress that late changes to the product may have to be relegated to a README file.

Localization

Will the product get localized? What does this mean for the documentation? Are there any requirements or standards from the translation agency? How will localization affect delivery?

Any menus, dialogs, toolbars, etc. — anything that touches the interface — needs to be changed. It’s easier to localize the documentation than the graphics in the documentation. Raise these flags at the beginning of the project, not later!

Extras

There’s documentation — the books, manuals, help — and then there are extras that you might provide. These include quick reference cards, video demonstrations, Quick Start Guides, and other aids. Think about Knowledgebase content, training, and other assistance as well. Extras don’t have to be part of the first set of deliverables. Your plan is there to show other team members what’s possible and doable with the resources you have.

With this information, you’re ready to start estimating the time needed.

Process, Estimates, and Schedule

Estimating, scheduling, and tracking require extensive discussion, which will be the subject of a future post. However, the information below provides a good starting point.

Milestones

Pay attention to the development schedule’s milestones. Link your deliverables to theirs. I get much better responses to reviews when I “chunk” topics so that they match a development or testing milestone. For example, if development plans a release that includes validating input, I match the documentation to that so reviewers can test both the software and the documentation.

There are many, many methods you can use to estimate your work. The best method relies upon historical data culled from similar projects. Don’t make an estimate based on anything similar to the famous “Seven Hours per Page” estimate that’s been bandied about since the late 1980s. That’s an old figure, an average figure. It was created based on limited data, where the publishing systems and software we have today didn’t exist. Throw it out. Another rule — never, never, never build or commit to a time frame in a meeting unrelated to scheduling.

The only estimate that makes sense is the one you come up with based on real data. I’ve been in many meetings where someone threw their Excel spreadsheet up on the screen and asked me, “When can you have a first draft?” Don’t answer. Explain what goes into estimating. Commit to a date for the estimates and schedule, but don’t commit to a schedule itself.

Don’t forget to include production milestones. If you’re still providing hard copy, printing, binding, and shipping take time, and you must inform stakeholders of the time frames and dates.

Reviews and Approvals

Describe the review process. Will it be a hard copy, PDF, or another method? How will you handle queries and corrections? You may already have a defined process if you’re working in a regulated environment (FDA, FAA, etc.). Be prepared to work with your reviewers to make the process smooth. Establish a ranking system for review comments. Some comments are suggestions, and others are about errors in the document. Tell stakeholders how you rank comments, describing which take priority and how you’ll deal with them. Show and explain so-called “Drop Dead” dates — the last time you can make changes and meet the schedule.

Resources

Documentation Team

List the names, roles, and responsibilities of everyone working on the documentation. Include notes on vacations, leave, etc., and who will pick up their work.

Other Teams

List the groups and POC (Point of Contact) in other groups, such as Development, Testing, Sales, Marketing, Support, etc. List each group/person’s responsibilities. Include those outside the normal reporting structure at your company, such as translation agencies and printers.

SMEs

Who are the Subject Matter Experts for each feature set? Don’t just list them; let each of them know they are included. Include dates if you have a good idea of when you need to interview them and when their documented feature is up for review.

Hardware, Software, Tools

You likely don’t need additional hardware. If you do, list the reasons why. List the software you are using to create the documentation. If you need a new tool or software, highlight this as needing approval before starting the project.

Existing Assets

Can you use any existing assets, such as a database of existing data, to create realistic examples? Are there existing graphics that you can use? The group that performs testing, verification, and validation on the software may provide sample data you can use.

Potential Risks and Issues

Any project can go south quickly. Be sure you identify any risks and potential issues. Give some thought to how you and the team can mitigate these. For example, if there is a real possibility that some features might not be included in the initial release, how can you keep it out for the release and slip it in later? Offering solutions is part of your job, as is negotiating a resolution that all stakeholders agree on. At this stage, your job isn’t meeting the schedule. Your job is to offer a complete plan that includes contingencies. Meeting the schedule comes after approval.

You can cut scope (good), cut the number of drafts (not so good), or add more resources (OK, but it matters when you add them). Are there issues outside of your control that affect your progress? If development uses a new source control system or a new development environment, scheduling glitches could occur. You can’t fix them, but you can alert stakeholders to what these delays mean for you. Talk with other functional groups to see if they are affected by these or similar issues. A delay in one group often ripples through to other groups.

Summing Up

If it all sounds like a lot of work, it is! However, the effort you put in at the beginning will result in fewer surprises, a better project, and better documentation for the end user.